Given the climate and the advent of spring here in Texas, an exhausting goal seems in order. Maybe it’s my simple form of protest to the trending zeitgeist of paralyzing fear and anger, despair, and confusion. Or it’s grief, perhaps, which can make us want to lash out. Break out of this figurative constitutional crisis.

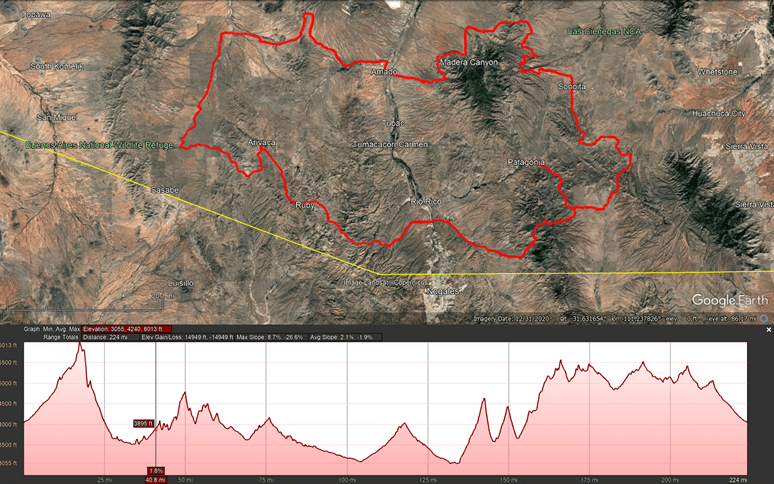

Texas isn’t a bad place for waiting this thing out, but it’s still just Texas, and there are no mountains to really speak of for 800 miles, and having had this bikepacking trip on my mind for a while, a route in Arizona popularized by a gravel cyclist and writer, Sarah Swallow. The 240 mile loop with 80% gravel sounded pretty challenging, and takes one to some of the more remote areas of the Arizona-Mexico border region. So I dediced, before I start a job and/or before my daughter comes to visit around spring break, I would make an attempt at this route.

The main goal is the loop, leaving from Patagonia, Arizona for 240 miles of desert fun. Generally speaking, it may be 40 miles between water [n.b., not an exaggeration]. This route was put together by Sarah Swallow and others, and is viewable, with background material, at:

https://ridewithgps.com/routes/26902258

The yellow line is the Mexico-USA border. The red line is the route. That’s the “full” route, and there is a lesser 174 mile route, which goes north around Madera Canyon, where there might be flowing streams after rains. Patagonia is labeled in yellow, being the turned in tail.

Departure

The jumping off is always challenging and fun. I gathered my gear and got it set before I stuffed everything in my Mother’s blue Hyndai Kona and blitzed west across Texas through a sandstorm and a headwind.

My mind, on this drive, was focused on my intention, which was a strangely conscious rebellion against the loss that I’ve felt in the last year or so, and the general mood. My instincts say that I should fight the prevailing mood and just fucking do something, do something difficult. Don’t be an American’t. Fuck that shit. Go ride. Move.

My mother passed last October. She was not a woman one could really have a deep and meaningful relationship with, and trying to understand her life leaves me with feelings of loss, sorrow and confusion. She seemed to often want to crush my Father down into the ground, which she accomplished, then going after. It seemed a principle of her existence that life was suffering, so we should make it so. A full three years before she died she could not remember names, frequently sundowning into a dark world where she could not find her loved ones and was trying to find her childhood home. This was well before the second hip fracture, which ultimately ended things. She insisted on living alone with her 12 or 15 cats in a disgusting nightmare up until one and a half years before her passing, a series of falls finally allowing her remaining family the opportunity to find her safer care.

The grief of losing a loved one, a parent, to mental illness lasts a lifetime, as if the parent was sometimes there and often absent.

The passing of partner’s mother on my birthday this winter was decidedly different. She was a conscious and loving being and was involved in the lives of many people. It was her guiding principle to bring people together and make good things happen. She was a complex and strong woman with soul, and I had treasured getting to know her, but the family had just experienced loss with the unexpected death of her son, just nearly now two years ago.

With this baggage and the future of democracy in question, I found myself west of the dust storm by evening, and past El Paso by 11pm. Then it was west into Arizona. Deming, New Mexico became the goal before I would allow sleep.

I-10 through west Texas has some beautiful stretches, and once past the hill country, follows the historic El Paso railroad line that prompted the Gadsden Purchase, being part of the second transcontinental railroad, which linked up in Deming, New Mexico in 1881.

Stop at a shockingly interstate highway rest area out there in Big Bend, Trans-Pecos country and there is likely to be a line rumbling past.

After a nap, it’s Sierra Vista, New Mexico soon after dawn, then Patagonia and I’m off, after pulling up in front of the community park bathrooms. The weather is surprising, as it’s only a little chilly at 9am. The forecast was for highs in the 70s, this warmth suggests some heat later in the day. The desert will heat up.

The NWS also had a graphic about the ongoing drought and general bone dryness, with relative humidities uniformly below 10%. I’m distinctly aware of the dryness in my sinuses, mouth, and throat, and my water consumption becomes constant. I’ve backpacked across several low and high deserts and this particular desert is shockingly dry. It’s March 20.

While I respect the desert, this one makes me a bit guarded, as it’s obvious that no streams are running. The blog mentioned running streams in March, but not this winter, reflecting the regional trend. The northern and central Rockies got snow, but not down south. Also, water caches are surely not a thing, if they ever were, this close to the border. [n.b. this ends up not being completely true.]

Cycling and bird watching are key visitor industries in Patagonia and it seemed like I was in a bit too much of a hurry to leave town, but the first day on this ridiculous route becomes technical, with a climb into the sublime San Rafael valley that drains into Mexico, then back over the Santa Rita ridge into the Santa Cruz river valley, where the route crosses the interstate at Rio Rico, my destination for tomorrow morning for water.

While this first bit of the route quickly becomes punishing on the climb over Red Mountain, for a while it’s the gravel of your dreams, undulating gravel roads with shady live oaks. So soon after departing I was riding in blissful comfort, all of my gear working well, after a few tweaks here and there. This didn’t last long, and I knew what was coming thanks to a blog that I should reference here.

The Santa Rita range deserves attention because it forms set of three distinct ranges with connecting ridgelines. The route thus far penetrates deeply into the more southern of the three, closer to the border. While the northernmost ridge of the Santa Rita’s is somewhat larger and higher, including Mount Wrightson (9,456 feet) and ecological wonder Madera Canyon, the southern Patagonia Mountain and the Atascasota portion is expansive, with Patagonia is nestled in a low valley between these two ranges.

The terrain is volcanic, and I am soon at home, meaning that I’ve lived on a volcanic Island, Hawaii Island, for 25 years, and the rocks themselves are familiar. I’ve long grown tired of walking and riding on volcanic terrains, but such is my lot.

The trail ramps up, and soon I give up on grinding 15% grades of chunky gravel. Up and over, and by evening I am past the nasty bits and on the downhill, where I camp before the road leaves the NF, along a wash, in a grove of dormant, leafless mesquite trees. The area is grazed, and the cattle clearly have soil impacts, churning the desert floor into a margin of several inches of syenitic sand and dust. It’s not a pleasing biome, devoid of native plants (until the rains) except for the charming ocotillo and barrel agaves. That’s in contrast to the live oaks and junipers back up higher.

Okay, as a courtesy to the reader, I will now try to be concise and discuss the Sky Islands

ODD ih C. Not much sea, some odd.

The second day confirmed my suspicions, that my 42s were too narrow for this loose unpacked gravel, composed of local basalt. It is very much like riding on the Big Island And with the number of 15% plus sections, I am walking frequently, and it soon gets warm in the mid-morning. By noon I can see Mexico, mere miles away. CBP is ubiquitous on the ridgelines, in their tinted trucks and topped ATVs. In fact, by early afternoon I’m realizing that I’m too slow, on average, and the full loop would be into a 6th day, which I could do, but my body is realizing that it’s probably too much too.

So I try to relax, make progress, and enjoy the day, a ramble through the Atascosa Mountains. As the sun is going down, I am not so foolish as to refuse two small water bottles from a CPB officer. In this area, cycling is popular, and the Border Patrol officers are plainly used to seeing cyclists. The atmosphere is kind of intense, sometimes, between vast stretches of Juniper and Ocotillo untouched desert and Oak/Juniper Savannah.

The hard day is rewarded with a long fast section through Oro Blanco and into Arivaca, a lively little hippie-rich town. The general store has everything, and knowing that bikepacking is popular here, I go to the rear of the store, where there is potable water and a porta-potty. I water up, now full 5-liter capacity, and eat my turkey sandwich before riding into the desert night, climbing away from Arivaca, where I am, again, astounded by the lack of human activity in the desert. Suddenly, there is no one but myself. This night ride is blissful. As the air cools in stillness, it sinks into the washes, moving downhill. This mountain breeze can make mountain towns particularly cold nearest dawn. As the roads drop in and out of the washes, I’m shocked by the contrast, in some places more than thirty degrees.

This third night I night ride to (La?) Fraguita Wash, where the ground is scattered with brass 5.56 mm. All night long there are no vehicles and the desert is sublimely quiet.

The fourth day is to and past the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge which has one of the most picturesque visitors center anywhere, several white adobe structures with a brick plaza between, and a picnic area below the main building. The volunteer insists I watch the movie, which is noteworthy. It starts with the history of failed attempts to pasture cattle in the high desert (4500’). The movie drives home the idea that rain does not like to fall in the desert. Reservoirs were built to capture what rain fell for cattle, and in major floods they failed, reshaping the valley. Eventually the land was purchased and donated for the Refuge, where the re-introduction of the Bobwhite was achieved in the 1970s and 1980s, and it still operates as a breeding center under the FWS, although the volunteer expressed concern over its future, as they are understaffed and all employees are casual hires, with no job security. But still they put on Federal uniforms every day.

The fourth day is to and past the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge which has one of the most picturesque visitors center anywhere, several white adobe structures with a brick plaza between, and a picnic area below the main building. The volunteer insists I watch the movie, which is noteworthy. It starts with the history of failed attempts to pasture cattle in the high desert (4500’). The movie drives home the idea that rain does not like to fall in the desert. Reservoirs were built to capture what rain fell for cattle, and in major floods they failed, reshaping the valley. Eventually the land was purchased and donated for the Refuge, where the re-introduction of the Bobwhite was achieved in the 1970s and 1980s, and it still operates as a breeding center under the FWS, although the volunteer expressed concern over its future, as they are understaffed and all employees are casual hires, with no job security. But still they put on Federal uniforms every day.

The Buenos Aires Wildlife Refuge has a gorgeous visitors’ center. This is the patio area below the main building.

Curiously, the movie noted a migratory bird, the Rufous-Bellied Thrush, but I was already watching one outside the window of the movie room. I mentioned this to the chatty volunteer, who was pleased. I left a few dollars to support this place and said a silent wish that they survive the Republican administration and continue their important work.

https://www.fws.gov/refuge/buenos-aires/species

The Mendez Wash valley is basin-like, draining to the north into a morass of intersecting washes, probably very similar to thousands of desert valleys to the south. Here the route turns more or less directly perpendicular to the border, or north-northeast, where the riding turns soft. The refuge facilities are located at the head of the wash, along an old mostly submerged (in sediments) ridge that produces a spring and seasonal lake. Once I leave the wildlife refuge visitor’s center, there are no more people.

It’s hot this day in late March, and the barn miles north at Segundino (second well?) is welcoming. No water, though, although there is a big tank, one of several this route passes. None of the several tanks I’ve seen have available water, and certainly there are various reasons for this. I wonder, however, if their cattle leases on NF lands also give them water rights. As I nap a dust devil sets off, rattling the roofing before it rips away from the barn, skittling northeast with the wind.

There is another section of fun, fast desert riding before we turn east, crossing dusty dry wash after dusty dry wash, down the Mendoza wash. Here there area is grazed into oblivion, with only the mesquites and ocotillos surviving. The desert floor is churned into a four inch layer of dust and silt. One section of dust is ankle deep, and I carry my rig through.

Since the second day I’ve been aware that my tires are too skinny for this terrain. Now it’s punishing, with inches of silt covering everything. It’s so dry that it is a loose powder, and pushing my bike through it doesn’t seem to get it any dustier. I wonder if there is a geomorphology term to describe all of these intersecting drainages, all delivering colluvium into flood basins, where now hooves churn into a regolith, like the lunar surface, which is formed from the impact ejecta of billions of years of being struck by small solar system objects. Or, maybe, there were cows on the moon once.

Before the turn to the east this is the closest this route comes to the Baboquivari mountains, and the Baboquivari peak, the monolith across the valley, behind which the white pimples of Kitt Peak National Observatory, operated by the NOAO, can be seen. These mountains are Tohono Oodham people. My topographic map says the name of the peak is Mundo Perdido, or lost world. A name this interesting means that I should return, and by now I have decided to do the shorter route, avoiding the northern portion around the Santa Rita mountains proper, the part with Mount Wrightson and Madera Canyon.

Wikipedia has this to say about Baboquivari Peak Wilderness: “This mountain is regarded by the O’odham nation as the navel of the world – a place where the earth opened and the people emerged after the great flood. Baboquivari Peak is also sometimes referred to as I’Itoi Mountain. The O’odham name for the peak is Vav Giwulik. Vav refers to a basalt outcropping (as opposed to the more general do’ag “mountain”).[5] Giwulik (also spelled kiwulk or giwulk) is a stative adjective meaning “narrow/constricted around the middle”.[6][7] The O’odham people believe that he watches over their people to this day.[4][8]”

https://www.surgent.net/highpoints/az/range/baboquivari.html

Sometimes deserts are truly punished and sorrowful places. But not just any desert. The great thing to appreciate about deserts is that they contain life, and the varied types, their adaptations, and mere presence will often surprise. Life finds a way to survive. As we do. That spark of energy, of life, in the desert is palpable because it is less common, and has often given me strength. It is encouraging, and buoys one with optimism, as long as death is kept away.

Often that desert life is crepuscular or nocturnal. But it is always present. But some deserts are not healthy, true of any ecosystem, of course, but in this case the landscape was dominated by mesquite trees, defoliated mesquite trees, such has been the drought in this area, and a barren dusty surface. What little grass had grown here had been grazed long ago, and the cows had likely defoliated the trees. A few ocotillos survived, but what little fat this land could provide in the form of plant matter that cows will eat, was gone. Essentially, in this area, whatever extant ecosystem now represented by the ocotillos had been completed replaced by mesquite and cattle, and the seed load of opportunistic invasive grasses that only grow after the summer monsoons or the winter storms. Little wildlife finds a home here, no lizards and relatively fewer insects. The potential animal communities desribed by complex and infinite interactions with themselves and other organisms, all gone here. This loss is real, and results whenever humans interact with their environment, meaning, always. Buenos Aires NWR re-introduced the local bobwhite variety, a keystone species responsible for seed propagation and trophic flux, in this case a process of being a frequent dinner for predators.

This space gave off a sense of loss, as it was an empty space in ecotistical terms, and was quite different than most of the route in that way. Other areas had cattle, particularly some areas near the border, but the grass there was relatively lush, and it was clearly not overgrazed. Perhaps it was the contrast between the Buenos Aires Wildlife Refuge lands and the leased areas outside it.

Beyond around 2015, my mother’s sense of self took a more dramatic departure from reality. Her absence, her passing, therefore did not happen at her death. In fact the loss of the woman I called Mom was seemingly constantly being eroded by mental illness, manifested primarily as her fear of interacting with the world. The evaluation of her mental health she cleverly and stubbornly avoided. In her world she maintained that there was nothing wrong with her, and if you had a problem with that, it was your problem, indeed this was evidence of it. The space in my heart for my mother was not a new space since her passing.

This desert, by which is specifically meant the stretch between the wildlife refuge and the higher, ungrazeable areas of the national forest, is one of those punished deserts. This is similar to the Pacific Crest Trail north of Mount Laguna, where there is nary water nor a tree in sight for 15 miles or so. Some deserts are punished by the sun. Often they have poor soils, in which no tree will grow. And when the natural ecology is absent, the desert can really be a dead place, except for cattle, who here consist of a dense 50-head herd, clustering near the one water source I see. In places like this that are incredibly marginal, it seems to make little sense to graze cattle when the ecological impacts are total. And the profits are certainly marginal too. With no rain, the grass has already been grazed. What do the cattle eat? The rancher would have to make the decision to move them or feed them or watch them die, at some point.

In Hawaii, a rancher confessed to me that their net profit was $40/acre. That’s in Hawaii, where the grass grows year round. So why are we destroying the desert for pennies?

That has never made sense to me, and the damaging impacts of grazing arid lands in the American West are well-documented. Add to the mix the impact of dryland desertification, as no where, perhaps, in the world are the the effects of climate change more apparent than in the American West. Dryland desertification is a thing, and grazing cattle on these lands only makes things worse.

The prospect of eating a juicy hamburger appealed to me, however.

After slogging through miles and miles of soft track, and one old water stash of gallon bottles, some full, strewn around, the route finally enters the National Forest and the desert seems healthier, again.

Here’s an April 2025 drought map from:

https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?conus

The Fourth Day

This day is composed of part of the route from past Buenos Aires to Green Valley, for most.

Let me get to the heart of the matter, to the reason you are reading. Because, if you are reading this you are interested in riding this route, the Sky Islands Odyssey. On the end of this fourth day I had done some epic riding, and ended up inside the NF above the Santa Cruz valley. In this area, few people go up into the backcountry when it is so dry, and the only lights from homes are miles away. In fact, I rode through the town of Green Valley an hour before I made camp, soon after seeing a headlamp off to the north belonging to two bikepackers who, I find out, left the same day I left, but had always stayed slightly ahead. Now, I passed them int the dark without their knowledge, about an hour after hitting the mercantile in Green Valley. Just before I had ridden through an immigration checkpoint.

The camp was dusty and right beside the road, but I was exhausted, and soon melted into my pad. That desert night was sublimely quiet. I looked forward to making my car and finding some cold non-alcoholic beverages.

The Fifth Day

The 175 mile version of this route goes through another part of the Santa Rita mountains, the Patagonia Mountains. This terrain really is described as consisting of various volcanic drainages at different elevations, with steep little basaltic volcanic plug remnants forming the peaks, where sometimes, if you were high enough, there would be pines and even a few firs. If you were low enough, there are no trees to speak of except the leafless mesquites, if there is water as in riparian areas there are some cottonwoods. And plenty warblers of various kinds.

Here’s the link to Sarah Swallow’s vastly superior write-up of this reoute, which she calls the (Sky Islands Odyssey) West Loop.

This return portion of the route takes us eastward, away from Bocumquari peak, and more or less over two large ridges, but not high enough to have much shade in parts, and there are not oaks. This is a dramatic route, preferred by cyclists who ride out of Patagonia for day rides.

At one point I heard a vehicle and moved off of the trail, as the dust was becoming bad from ATVers, the count was probably 15, many of which were going to Green Valley for breakfast. At this point my fatigue is pushing my envelope and I think some are concerned with my welfare. The vehicle is a high cube height Transit van, painted with a logo and the words Universal Pro Cycling, or something similar. Soon after came the universally pro cyclists, dressed for the road on electronic shifting carbon fiber gravel bikes, looking extremely well-groomed as well. We discussed gear, and chatted, and they talked about their crazy driver.

The reward for this day of punishment is one of the longest downhills of the route into Patagonia on Salero Ranch Road. This Sunday morning had many riders doing the out-and-back from Patagonia. There are so many riding choices in this area.

So here’s my thesis, your reward for reading this far.

This route is perfect for supported group riding. There are so many steep sections that riding it with overnight gear, and food, and 4 liters of water, significantly reduces the potential enjoyable of riding this route. And riding with support would probably allow completion of the full 240-mile route in five days. There are also many paved road crossings, many gravel roads are very driveable with a 2-WD car (but don’t get stuck in the soft stuff!).

And, ride it with fat tires only.

Finally, the synopsis. On the way back to Texas I hit some sites and drove roads that I had always wanted to drive, mostly quite close to the border. Over time, on the drive, I developed a cough that I attributed to the dust, and I reminded myself that I should have had a face cover of some kind. These dust particles are mostly not terribly small, they settle out readily, so I wouldn’t need N95. I had plenty of time to think about this on the 1,100 mile drive back to Houston. After my arrival in Houston, however, I just got worse, and I was soon sick as a dog, coughing my lungs out. I put two and two together and finally realized that I had Valley Fever, a fungal lung infection that could be fatal. But if it isn’t fatal, you survive, and life goes on. My treatment was for pneumonia, as they don’t know about Valley Fever around here, and didn’t want to test for it, which would have required work. Instead it was prednisone, an antibiotic, and albuterol, which did the trick.

Here are the key points (please see below for videos):

- Group supported riding.

- Fat tires.

- Face cover.

Kudos to Patagonia supporting cycling and allowing long-term free and safe parking.

Finally, here is the link to the route I rode.

https://ridewithgps.com/trips/263881223

Cheers,

Graham Knopp

April 22, 2025

Houston, Texas

copyright Graham Paul Knopp 2025

videos follow, also on my Youtube channel “Graham Knopp”.

Please leave a comment. I will respond.