September 16, 2025

Copyright Graham Paul Knopp 2025

More immediately in weather news, not climate, I experienced my first Texas hail storm, and my car now has some dimples to show for it. I did not take action quite quickly enough to move the car into the garage. Standing at the front door, watching the pea-sized hail stones accumulate in the cracks in the driveway, I didn’t see the urgency, until a few quarter-sized stone started whacking the car loudly. Then I finally jumped, and as I was getting into the car to move it, one large hailstone found the top of my head. Ouch. No damage done, but I now have an appreciation for the simple, raw violence of a hail storm. Seemingly random, brought by some towering plume overhead that rises high into the atmosphere and then falls straight into the Earth, punching downwards on us little humans until exhaustion.

I hope this doesn’t completely turn into a climate change blog, but that will likely become a focal point.

FYI, what I bring to the table is not just interdisciplinary expertise, it’s also an understanding of math and statistics, geophysics and climate, oceanography and macroeconomics. That’s part of my added value, supplemented by a better-than-average ability to write and communicate these ideas, supported, most of all, by common sense and a broad perspective, a level-headed perspective.

At this point in things, we’re certain that climate is changing due to human activity. But, how is it changing?

What led to this inquiry was a more general question about what we can so about how climate has changed thus far, in the industrial age, as that’s when observable warming that was likely caused by human activity started.

I have lots of questions. Is the picture painted by the Deep Adaptation movement realistic? Is collapse inevitable (unless we restrict emissions more or less now)? Are things really changing that fast, and that badly? Let’s find out.

A complex system like the Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, and land, are all in contact through energy and heat, water, air, and the carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, among others. Complex systems find quasi-stable states. But if you push a complex system in a given direction, it will respond. It may limit the effects of the stressor, or it may find a completely new method of organization.

It’s my view that global climate has entered a different state already, and we will look at the research describing these recent changes. This isn’t to say, however, that the thermal forcing isn’t fast enough or strong enough to keep pushing things into other new states. That’s pretty likely.

And different components of a large and comples system may respond at different rates. The ocean receives about 90% of the increased heat from climate change, but it has a total heat capacity of about one thousand times that of the atmosphere, so it is much slower to change.

The climate alarmists, who most certainly don’t call themselves that, have particular criticisms of the IPCC reports. One of these is that they ignore the low probability, high risk scenarios. The “fat tails” in statistics jargon.

But we’re far enough along we should be starting to see some of these effects. And we are.

As an aside, we have to take note of the over-arching cultural context of these processes and events. The cultural narratives. What Yuval Hurari calls the intersubjective realities, the shared stories that give our society structure and order, and motivate people to go to work and raise children, or to riot. While calling human-induced climate change a hoax is clearly the work of engineered propaganda, as the oil and gas industry themselves were discussing how they were modifying climate as early as 1959, it clearly is a simple human trait to dismiss ideas that are hard to grasp. The movie Don’t Look Up tried to illustrate various aspects of this apparent clash in cultural narratives, including the propaganda, but it is unfortunate that Dicaprio continues to fly private jets everywhere, as if, in that particular actor’s case, the movie making gives him a negative carbon footprint. Maybe I can get carbon credits for this post?

As a freedom-loving American I’ve felt it’s my duty to be skeptical and question all ideas, including the powerful cultural narratives that instruct us as individuals what is best to do. A baseline for appropriate actions is set for us by these cultural narratives. They tell us to get a job, help our parents, raise our children, and support our troops. They also teach us that laziness is bad, drug use is below our social status, unless it’s with rich friends, and various status defining labels and judgements, depending on one’s particular subculture. It’s always been my belief that freedom-loving Americans should question everything, and so this exercise is a patriotic action, more beneficial than bootlicking. (The American predilection for being submissive and accepting what one is told, for bootlicking, flies in the face of this cultural narrative that paints Americans as freedom loving. I am, in part, referring to the Texan practice of dismissing human-induced climate change with, “Climate is always change, we just don’t know why!” *sigh.) One author (ref?) described cultural narratives as always shifting, throughout history, to change and support the dominant power structure, which suggests that our values may sometimes be harmful. This is a powerful idea, that cultures change their narrative to support what they are doing, sometimes to the point of delusion, which predictably leads to crisis. The point of democracy is to be self-correcting, so that conscious changes can be made, and new narratives can be chosen. But when problems are global and involve many cultures, some of which are in conflict with one another, that’s a next-level problem.

I’ll return to such ideas in the future.

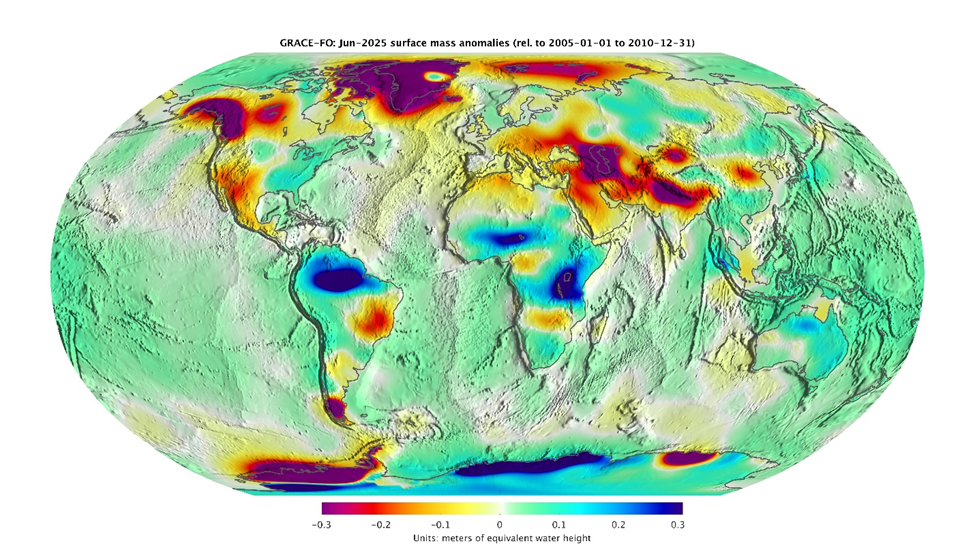

Now, here’s where we begin to discuss the GRACE/GRACE-FO (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment/Follow-on) mission data and analysis papers. This mission uses interferometrically linked satellites to precisely observe the Earth’s gravitational field, a process performed over many orbits. Over time this shows the movement of water within, and on the surface, of the Earth. Yes, long-term rain storms and droughts move enough water around to have an observable change in the Earth’s gravitational field. Pretty amazing.

The GRACE spacecraft launched to low-Earth orbit in 2002, with the follow-on launched in 2018. A third, GRACE-C, is planned for launch in 2028. This is a partner NASA and German Aerospace Center project. I can only assume the GOP administration doesn’t know about it yet.

I’ve been looking at two papers that analyze this data set, Chandrapurkar et al. 2025 and Rodell & Li 2023, the latter of which has a nice presentation available at:

Rodell & Li PowerPoint Presentation

This work looks at changes to terrestrial water storage (TWS). This includes all forms and locations in which water can be stored , stream flow, snowfall, infiltration, reservoirs, and soil moisture. Human effects are sometimes causing changes in these values. Pumping removes water from groundwater, and some of that is returned through infiltration, or it is evaporated, or it flows away.

Grace_extreme_final2_texttables.docx

This map shows the difference between TWS in June 2025 relative to the 2005-2010 baseline. It shows a lot of bad news. Central Asia and the Himalayas have been dried. And there is the western USA, which is another related issue that I will check back in on. We see losses in ice cover in Greenland, Alaska, and the Himalayas. Loss in ice cover results in more seasonality in river flow, with a stronger spring/summer melt and drier autumn.

I’ve written before about the warming of the American West, and still intend to look at ecological information relating to recent changes. To lowest order, however, one would expect to see climate zones moving up in elevation. The monsoonal moisture has unfortunately stayed farther east, so the American desert, by which I mean the Great Basin, Mojave, Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts, of course. The ridging issue I don’t completely understand, and hope to get into, but apparently we expect the northwesterly-driven jet stream to weaken and more ridging, allowing stable conditions to settle in. There is science showing how tornados have moved eastward. This is one somewhat local pattern that we can recognize is likely to be related to human-induced climate change.

There are some important details in these papers. For instance, the drying we see in the Pacific Northwest, Alaska and parts of Canada, are not at all completely due to ice loss. Mostly is fair, but these areas are drying without consideration of ice loss.

The GRACE data also show that the loss for TWS is net. That means that water has left the continents for the oceans. This is presumably mostly due to increased snow melt and ice melt, but pumping and agriculture have a small component.

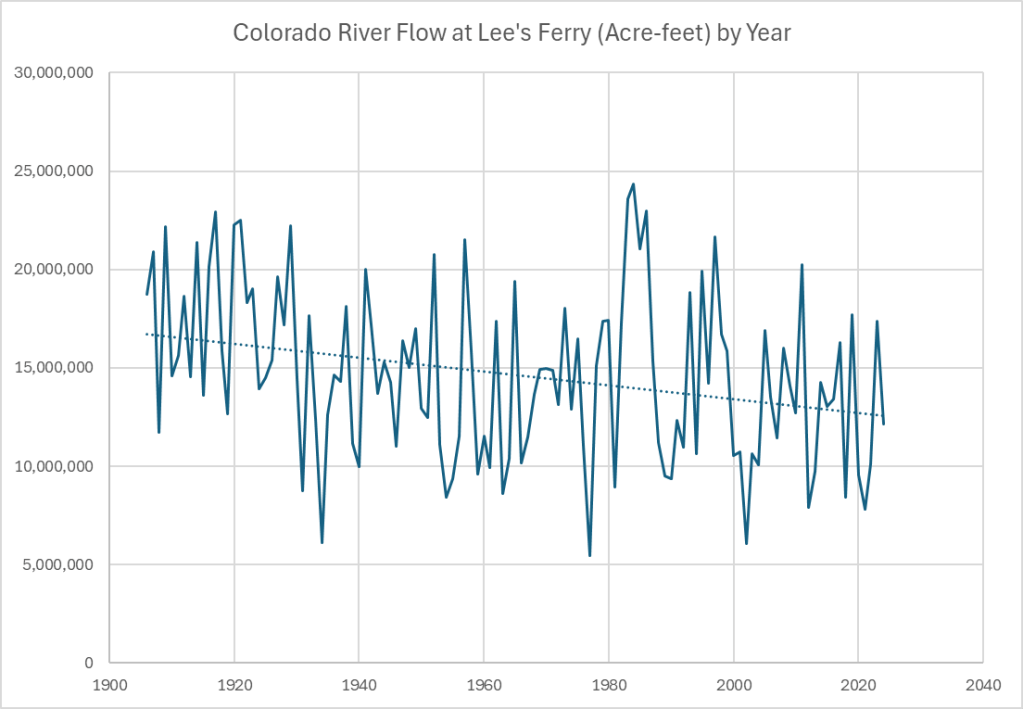

So, the American West is drying. One way of looking at this is stream flow. This plot shows average annual stream flow in the Colorado River at Lees Ferry, 15 miles below the Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona. This gage location means that the discharge is partly controlled by the dam, which serves to buffer short-term changes.

data from: https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/NaturalFlow/provisional.html

Clearly, the trend is negative, and the zero point of the vertical axis isn’t too far down there.

Now we expect this trend is a result of drought in addition to diversion and pumpage.

The Colorado River flow is fought over (in the courts).

Colorado River water is first divided up by the States (CO, UT, WY, NM, AZ, CA, NV) by the 1922 Colorado River Compact, dividing up 16.4 million acre-ft/year between them, plus 1.5 million acre feet/year to Mexico in a 1944 agreement. Suffice it to say, the 16.5 million acre feet per year is either not there, or is precarious.

80% of this water is used for agriculture. Now, this isn’t at all unusual, and it’s fair to say that urban users pay for the water delivered cheaply to agricultural uses. Strategic priorities.

There are some very interesting related stories.

For instance, the 1944 Mexico-US agreement says that the USA will deliver 1.5 million acre feet per year, but for some reasons Mexico has to do the same every 5 years. Why? Good question.

U.S. denies Mexico’s request for water for the first time in 80 years

Meanwhile Texas is suing New Mexico over Rio Grande water rights, although they are reportedly making progress towards an agreement. One could speculate that this agreement will involve teaming against Mexico’s water rights in some way.

The thing is, as we expect drying to continue, we can also expect these different stakeholders to tighten their grasp on water resources, resulting in predictably more cutthroat legal fights.

What happens to the 1922 Colorado River Compact and the 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact should be seen, as a whole, a test case of climate change induced resource competition.

The Colorado River has not flowed to the Gulf of Baja for many years, which isn’t really that hard to understand given that the American West and leeward Mexico are arid places containing many millions of people, tons of industry and military activity. The wetlands are reduced by 95% on the former delta. The best account of these wetlands is found in the writings of John Muir published in 1915, by the way.

Viewed in the larger picture of ecological change and dryland desertification, the American West is one of the first places on Earth to experience sudden climate change due to human activity. There is precious little acknowledgement of this fact, at least publicly. What is also clear is that there seems to be little interest to improve water resources with policy.

Please leave a comment. I will respond.