copyright 2025 Graham Paul Knopp

Parry’s Agave with crickets in the high Chihuahuan Desert at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Many of these plants had crickets so arranged. Is this normal? Is this because rain is on the way?

When you want to climb mountains in Texas, your choices are very limited to Big Bend National Park and Guadalupe National Park. From Houston this means a 700 mile drive.

So, in the interest of making this concise, the plan was to climb Guadalupe Peak, then do an overnight on the back side of the ridge in Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

I achieved both goals in spite of some wet weather.

My sixth and seventh drives across the State of Texas is perhaps only mentionable for a couple of observations:

Texas. 99% of it is vacant land, but if you live there, you might be stuck in traffic.

The Austin area appears to have replaced many of its churches with wineries.

The Guadalupe Mountains consist of a massive limestone reef upthrust about 25 to 30 million years ago. It’s mostly very dense limestone devoid of the karsty features one finds farther north in New Mexico that form Carlsbad Caverns and other caves. One feature of limestone is that it has no particular crystal form and fractures in any directions. So, not only is the trail surface very hard but it is also very irregular.

So, I had three days to spend in the Park, but arrived late on the first day, and did the Guadalupe Peak hike somewhat late in the day, arriving at the cool and windy just before sunset. This is an extremely popular hike, and I passed at least 100 hikers of all ages heading down while I headed up. The sunset was not spectacular, as tropical moisture was streaming up from the Pacific side due to several hurricanes off of Baja California.

Driving up from Van Horn is the way most people come. As one approaches, the massif of El Capitan and Guadalupe Peak come into view and then the road winds up into the mouth of Pine Spring Canyon. That’s where the Guadalupe Peak and other trailheads can be found and where I stopped.

Chances are you haven’t heard of this National Park, unless you lived in El Paso, in which case you likely had lectures on hydration and heat stroke and heat exhaustion, which is like heat stroke except your heart isn’t failing yet. The Guadalupe Peak trail likely can be quite hot and high exposure (on my climb it was 70s and damp). A search reveals a death on the summit on New Year’s Eve 2022, but that was from a fall. Correction, there was a likely heat death in 2019 on the trail.

Hiker dies at Guadalupe Mountains National Park, highest peak in Texas

Here’s an interesting list of reported incidents in and near the Park.

NPS Incident Reports – Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Before I went up, I had a chat with a young Park Ranger at the visitor’s center. She said that she had funding until the following Thursday (it was Saturday) through a local vendor. I said something about not letting the bastards grind you down, to which she responded, “I just want to help people.” My response to that was, “It’s too bad our government just wants to hurt people.” It wasn’t, actually, but I wanted to say that after, though I was too engrossed in their desk map, which had mileages, information missing from the maps they hand out. The Ranger suggested I visit the Bowl, “that’s where the spirit of the Guads is”, but didn’t offer any other information about the trails, nor any need for a backcountry permit. Pro tip: read the web site. I strive to be completely within the law when I hike, but if a ranger is not going bring up the permit issue when I tell them I am going into the backcountry, I am not likely to mention the issue either, though I did come to regret not asking specific information about trail conditions. For the record, the one time I was anywhere without a required backcountry permit and got checked by a ranger I did not have my backpack on me, having camped already, and talked my way out of it. But that was many years ago (in the Desolation Wilderness) and I always try to have a permit.

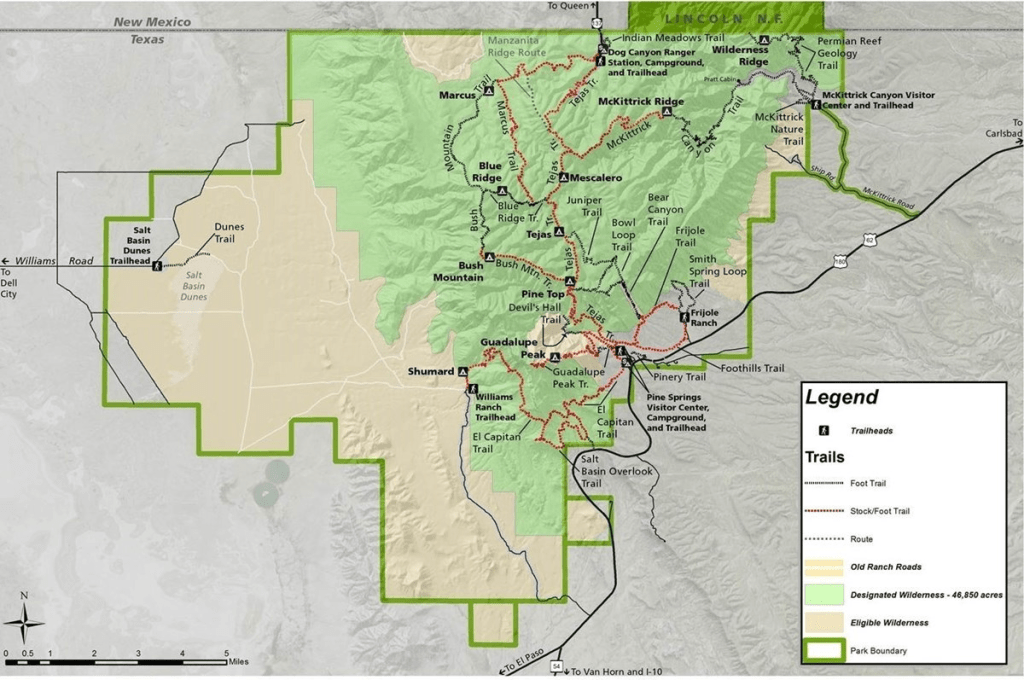

NPS Trail Map. With the shutdown, the McKittrick Canyon gate was closed, requiring an additional four miles one way, so the sensible access point was Pine Springs.

Up and down the Guadalupe Peak trail. Departing the summit after sunset. On the way down the air begins to smell moist – the arrival of that tropical moisture, and raindrops appear in my headlamp beam. And the wind blows and light rain falls for hours, but in the morning, the ground is not wet, the limestone rocks and soils having thirsted them up. Nearby is the wide and completely dry channel of the Pine Springs creek. Judging by its girth, this stream swells to a river on some occasions.

Pine Springs Canyon with the Permian Basin to the east. The NPS states that the Park is negatively impacted by air pollution. Today, not so much, but the previous night I could sometimes smell the Permian Basin O&G activities, the NOx and ozone, and other stuff.

To the west from Guadalupe Peak near sunset. The ridge on the right is part of Bush Mountain, where I’ll be in 24 hours.

The monument. On the right.

On the second day I departed late and started up the spectacular Tejas trail, which climbs out of Pine Springs canyon and Devil’s Hall near the head of the canyon. It may be more enjoyable than the Peak trail.

Let’s look at a GE view:

GE view looking roughly east. The night walk was along the ridge from Bush Mountain to Marcus Wilderness Campgrou.

The plan was to hang a left at the ridge top, climb Bush Mountain, then decide to proceed down the ridge to the north to the Marcus camp site, or turn back, either camping back at the top of the ridge or going home to the car and dry tent, if I was soaked. In the ebbing light from the top of Bush Mountain I could see a hanging wall of rain advancing. The choice was to go forward, eventually descending low enough to be dry enough to camp. Or, spend the night wrapped up in a tarp on the ridge. My headlamp batteries soon had to be replaced, as they had been dimming steadily. That done, I advanced down Bush Mountain soon to find out that the previously wide and graded stock trail was invisible under vegetation. GPS was needed to find the trail. And soon that front moved in and I was either in the clouds or in the rain just under them. Visibility shortened. The humidity fogged my glasses up instantly. Five steps, then refer to GPS to find the trail, then perhaps ten steps, and another GPS check. Then, a blowdown of fire-killed trees. A crawl under, then over, then check GPS to find the trail. Sometimes the GPS check would reveal I was on the trail, but the direction, the bearing, was key, in this ridiculously irregular terrain, always changing slope. Foot by foot I advanced. Soon these headlamp batteries faded, another mistake, as I had bought the cheap batteries at the store in Pecos.

[The burn blowdowns may have been from the Cutoff Ridge Fire in July 2023. There was also another in the Bowl in 2021.]

Foot after foot I shuffled. At one point a side trail jutted off, which I followed, only to discover rain going up and a sheer escarpment. Nope.

Now all this was by choice. I had wanted a challenge. I had anticipated walking in the dark and rain, but not without a discernible path. Not with a dim headlamp. Not in the clouds, with no visibility. But, in the end, it’s all just mileage, and, if you can walk, you can walk out of it. Hiking in rain doesn’t bother me unless I’m cold, and as this was a long, chilly slog, I wasn’t moving fast enough to generate much warmth. On the other hand, I grew up in Wisconsin.

The mind wandered as I shuffled. It went to road trips with my parents, trying to read a book in the back seat while they tried to navigate some suburb to find a notable home, likely a Frank Lloyd Wright design, many of which were, and are, found in the Chicago suburbs. This memory was years after those trips to Taliesin near Spring Green, or is it Mount Horeb? Anyway, out there past Mazomanie somewhere. But sometimes I navigated and became very good at folding maps. Parents though, so politically correct, children of the progressive 1960’s, never uttered a racist statement or point of view. Bless them. But they took it so far to shelter me that they never mentioned the Taliesin murders. I only found out about that recently, from Wikipedia. It makes sense though, the interior spaces of that place were creepy and damp. Oh that, early memory of the restaurant over the stream. I loved that, and always wanted to go back. Maybe I will. But yeah, the murders. That might have spiced up those visits, stimulated my seven-year-old interest. Shuffle shuffle, with wet boots and wet feet. Here, in the in-between, again. The easiest way to go is through. I think I’m going to lose some toenails on this one. GPS check. Where is that trail? Let’s think about something lighter. Like that evening I cowboy camped, illegally, near the Tuolumne River in the meadows. Oh, I forgot all about that party Aramark had in the Tuolumne historic cabins. It was a sublime Tuolumne evening, with the sun setting over the meadows, which runs somewhat north-south there, and there was the sound of a muffled indoor PA, and tons of cars, some escalades with waiting drivers, a few partiers smoking cigarettes outside, name tags giving them away, some wearing suit and tie. But most everyone was boozing it up inside as I ambled past, wondering if I would be told to keep walking by a patrolling ranger, as my friend had, no camping near the meadows. At that time I had been really bothered by the party, but that’s Yosemite, nature experience on demand. Just a several hour drive north from LA and there you have it. The National Parking Service offers many levels of comfort. The Wawona, glamping, trailer camping. How much revenue does Yosemite generate per year? $20 billion, I heard. That’s an economic engine. But this little park has had little money for trail maintenance in the last 4 or more years…maybe it’s for the best.

It had rained the previous night, and was raining steadily, but there was no runoff. It seemed as if the limestone rocks were thirsty and absorbed the moisture greedily. The lack of perennial streams might well be explained by the geology. Streams certainly run when there is an adequately rapid rainfall, as the wide stream channels attest, but perhaps the many fractures in the limestone help to entrain runoff, and, chemically speaking, limestone will hydrate and dehydrate. So, it’s fair to say that the rock really is thirsty. However, there is a perennial stream in McKittrick Canyon, which means this area has probably been inhabited for thousands of years. [The NPS web site informs us that the Guadalupe Mountains were the “last stronghold” of the Mescalero Apaches. The Apaches weren’t the last to fight, that honor goes to the Modocs, if memory serves, but the Apaches fought harder than anyone, and were highly adapted to this place.

Mescalero Apaches – Guadalupe Mountains National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

In any case, as I slowly descended, perhaps at the rate of one-half mile an hour, the rain lessened and the air warmed, and, at around 1:30am, I made camp and slept solidly.

I had plenty of time to consider trail maintenance, as four years is a long time for a designated trail in a National Park to go unmaintained. However, the area may have been closed after the burn, a common practice to prevent the introduction of invasive species. As a reference I had Volcanoes National Park, which has many poorly maintained trails, particularly since Covid. It was easy to imagine a higher-up slicing trail maintenance funds, the reasoning being that hikers can just use GPS.

The trail itself was engineered to a maximum grade of about 10%, had buttressing in places, and was clearly built wider than a single-track hiking trail, but not as wide as a jeep trail. So, a stock trail, built not only for the animals that carried the supplies for the construction crew, but also perhaps for stock entering the high country for its green grass when the rains come. This trail had all of the characteristics of a CCC trail, including the dynamite blast marks and drill holes, but it had fallen into disrepair and neglect and now not even the vegetation is cleared to reveal the path. Near the Marcus-Blue Ridge trail junction an active landslide crosses the trail. But did I really read somewhere that these were CCC trails? It seems so, but the Park was only established in 1966 and opened in 1972. Before this time it was in private hands.

Clearly the summer monsoonal rains had been a factor, especially in the growth of perennials. My presumption was, as I got going that early morning, that the trail would now be easy to follow. But the trail was covered in thick stands of perennial wildflowers that obscured the once wide path of the stock trail, forcing me to again rely on GPS to find the trail from time to time. Fortunately, as I progressed closer to the trail heads and climbed back up the vegetation thinned.

From time-to-time silvery alligator junipers, seemingly luminous in my headlamp, would pass by.

At one point two eyes floated motionless not 20 feet away. Was I seeing something far away, having dropped below the cloud level? My answer was given with the thumping of two sets of hooves, jumping away. Mule deer, likely. The next morning I saw two of them down in the basin about two miles away, and perhaps that was the same pair again. But what were they doing on the ridge in the middle of a storm in the night? Perhaps drinking rain water off of grass leaves? Other critters had been rare, and include rabbits near the visitors’ center. Scat was rare and included some that I could not identify… a medium sized mammal like a bobcat or fox, perhaps, a few coyote droppings, but little else than vulture droppings on the ridgelines, the long periods of dryness making most of this wilderness area prohibitive to life. Apparently, there is a perennial stream in the Park, in the shutdown-closed McKittrick Canyon.

That’s the meat of that hiking story, without being too much like one of those thru-hiking blogs in which the reader learns that the hiker ate raisins with their oatmeal, and then had a good BM.

The way out climbs back up into the montane country, and I’m doing double-takes when I see particularly unexpected tree species representative of mountains far away. With the continuing light rain, predictably starting as I climbed back above 7500 feet, it was a bit lush, the air was damp, with maples just beginning to yellow. Past blue ridge the trail traverses a dry stream, which is insufficient to describe the 20-foot-wide flow channel, indicating what must have been near-cataclysmic floods.

For a second I started to think about the most damaging plants I had encountered, the most prickly and the ones that had gouged my shins the most. One desert plant was the clear winner, the humble creosote bush. But not the cholla. One learns to always give the chollas a wide berth, and it seems strange to mix a marine idiom with a desert plant. It’s true, the trail never goes through a cholla, so if you are walking into a cholla, you are not on the trail. Fact. Strangely, I hadn’t seen the Catclaw Mimosa. At the Visitor’s Center there had been a Catclaw Mimosa with a sign before it. None of those, until the moment I thought of them. Young, thorny small trees with plenty of long thorns, right in the trail. Stop thinking, perhaps, I thought.

On this short trip the only other hikers I saw were near the top of the Tejas Trail and Pine Top for a total of three.

For the record, what the NPS says about trail conditions on part of my route:

“The Bush Mountain Trail is a major artery of the trail system, leading from the Tejas Trail above Pine Springs Canyon all the way to Dog Canyon. The trail loops far to the west to wind above the cliffs on the western side of the escarpment, then descends through the isolated northern portion of the park before climbing back up to terminate at Dog Canyon. The Blue Ridge allows the Bush Mountain Trail to be done as northern or southern loops.

…

The northern portion of the trail beyond the Blue Ridge junction is infrequently traveled and may be challenging to follow when overgrown with grass. Cairns mark the route. Hikers should have a compass and paper topographic map in this area of the park and be prepared for route-finding. “

Trail Descriptions – Guadalupe Mountains National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

These are facts. For the most part, because cairns mark only part of the route.

Photos and a couple videos to follow:

At night these junipers were wet, shiny, and seemingly luminescent.

Colorful snail.

Wildflowers.

Early fall foliage at an elevation of around 8000 feet.

Kind of lush at the edge of the Bowl.

I took this because I thought one would be able to see the tiny raindrops up there in the clouds.

Climbing up the Tejas Trail, the clouds were rolling in over the Guadalupe Peak ridge.

This really doesn’t do it justice.

Please leave a comment. I will respond.