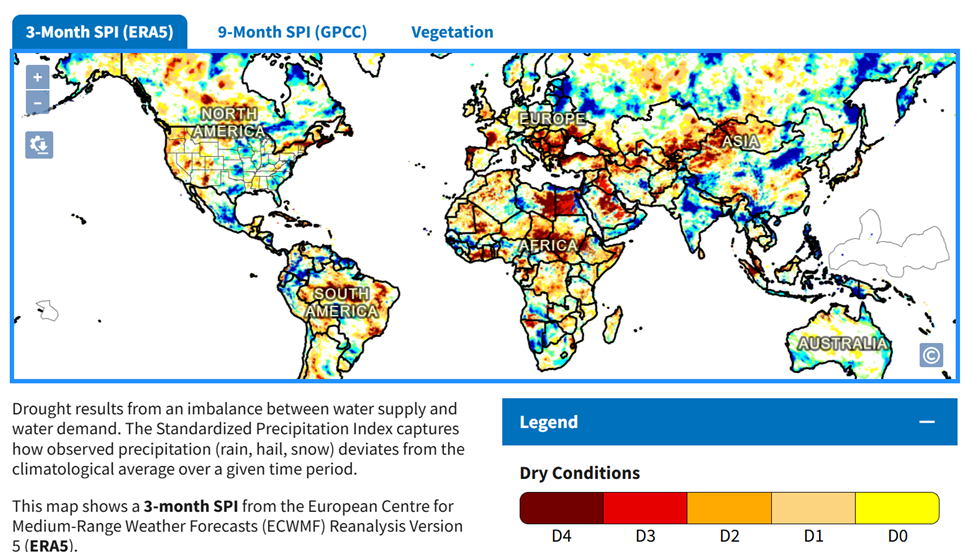

Observing the global drought monitor, it appears that much of the world is in drought.

There are significant parts of Europe, central Asia, Africa, South America, and North America in significant drought (D3 or worse).

While the USA drought map shows somewhat improved conditions in recent weeks, particularly in California, the situation still looks egregious in many areas:

Now, one might take that information and speculate that such a drought might well have an impact on agricultural productivity, and affect their markets. We would expect prices to rise if supply is impaired by drought.

Let’s test that hypothesis for wheat, soybeans, corn, cotton, and sugar, as they are globally traded commodities and should be affected by widespread drought.

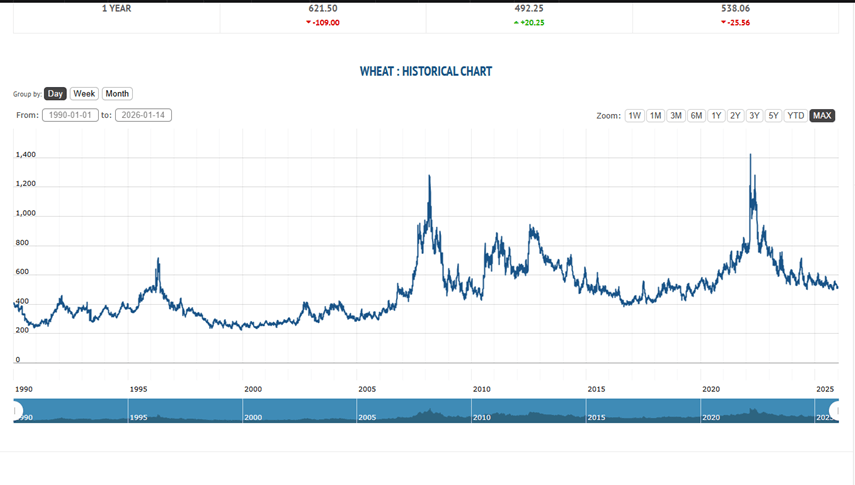

Here’s price history for wheat from 1990-2025

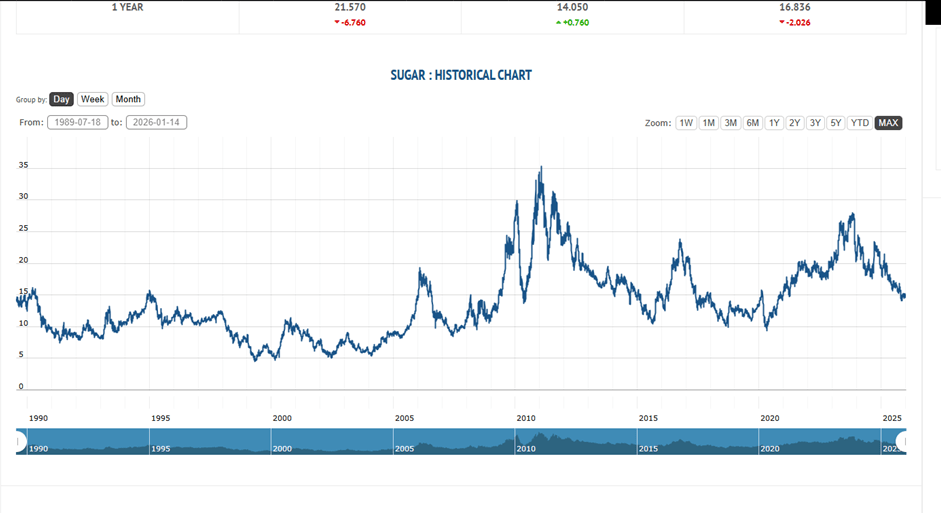

The prices for these commodities largely show the same behavior, settling after COVID supply shocks to new a new international supply/demand equilibrium. Stable prices allow more marginal producers to find markets, as well, so we expect long-term price stabilization in which a new price is approached asymptotically, until the next perturbation happens. Of course, costs are always changing and there are seasonal production curves somewhat lagged by storage, so the ideal of a hypothetically stable price equilibrium is always being altered by changes.

The ratio in present to historic pricing for these commodities is around 420/240, or 15/10, or 550/300. The mean of these is around a 70% increase (although remember that each curve is the product of crop-specific history, trading, etc. trends). Dollar devaluation is part of this, and so are energy costs, which, in fact, well-represent the behavior much of these three curves.

The only part of farming that doesn’t involve energy costs is the sun, rain and soil. But all of these require space, so land costs are inclusive too.

In any case, internationally traded agricultural products, indeed the cheapest of all agricultural products as they are produced at the greatest scales, are still settling post-covid, but remain well-elevated above historic values by around 70%.

Whether we see a minimum soon and a rebound will be determined by supply. And whether that supply is constrained by widespread drought will be seen, and this will be revisited. Irrigation plays into this, as it can buffer productive regions against drought. With long-term drying, however, this is a losing game and producers will soon find costs rising.

This can be seen in context of global climate, and global markets are impacted by global climate. Given that long-term widespread drying is already well-described in various regions in the GRACE/GRACE-FO papers like Chandanpurkar et al. (2025), we would anticipate increased irrigation costs to be a factor, but lower-powered than energy costs in the pricing equation.

let.iiec.unam.mx/sites/let.iiec.unam.mx/files/sciadv.adx0298.pdf

The longer-term implication of long-term drying (and desertification) is that ultimately regions will not be productive and will not provide product to the international market, further raising prices. Regions will be priced out of industrial agriculture’s race to the bottom with over-production. (Now that vast areas of the Amazon River Basin have been converted to pasture, it would be a useful task to evaluate groundwater resources there.)

Apologies that the scales are not the same, but the energy spike of 2007-2013 is well represented in all the commodity price curves shown, as is the COVID spike. Given that oil prices are now around 2.5 times their near-historical average of about $25 bbl and about $61 bbl today, the huge conclusion is now made that energy prices are the dominant factor in agricultural costs, however the costs do not scale linearly with energy costs, likely because part of farming involves free energy from the sun, and free rain to boot, god willing and the creek don’t rise.

This means that resource scarcity from long-term drying is not (yet) a dominant factor yet in agricultural production, but with constant energy prices we may be able to see this effect soon when prices find their bottom.

Commentary: consumer prices have risen because energy prices have risen significantly from the year 2000, which have also experienced a ton of volatility. When people are surprised by increased costs, oil prices are to blame.

Next time: economics of agriculture, economies of scale and cultural heritage.

Please leave a comment. I will respond.